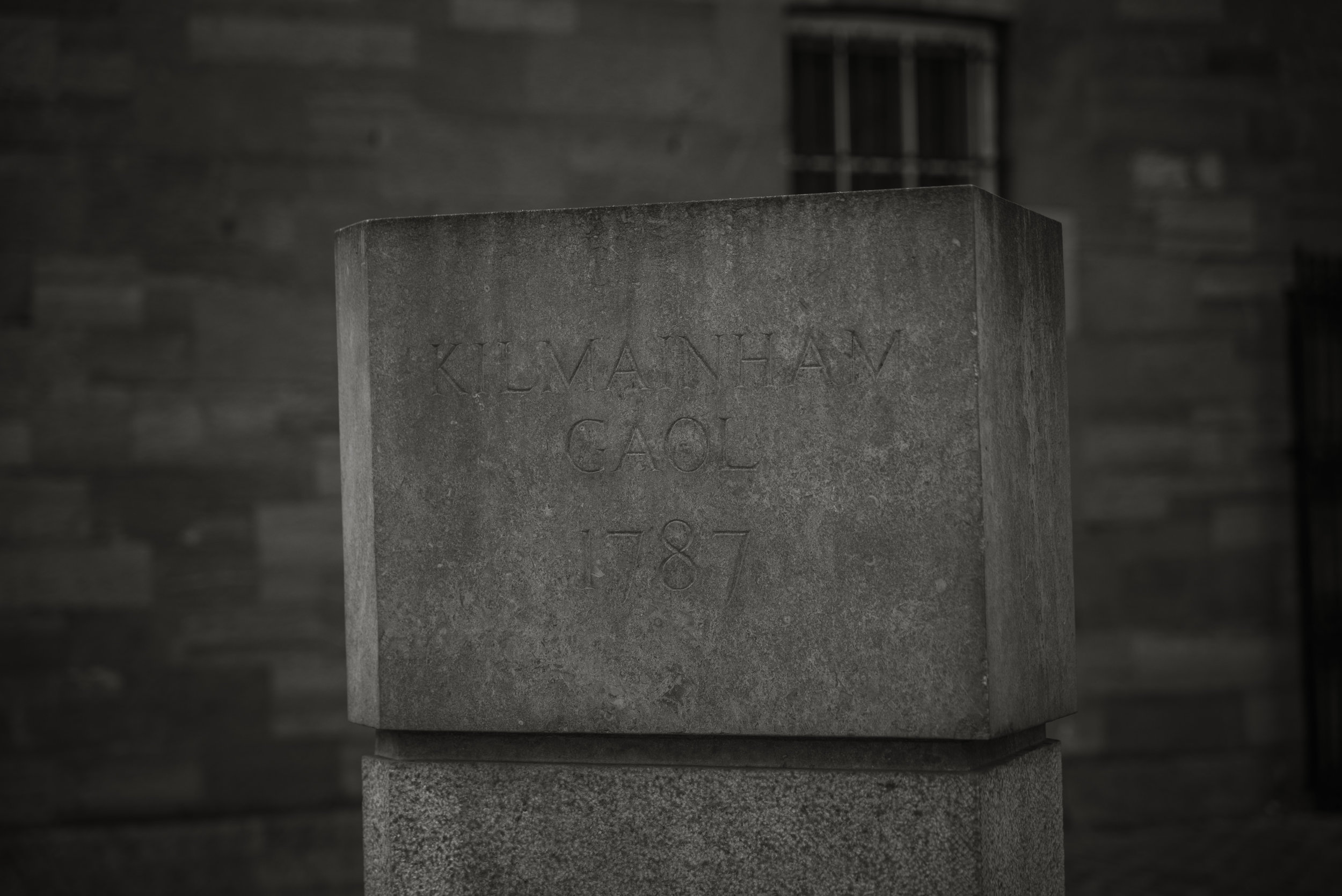

Kilmainham Gaol (pronounced jail) has been on my top lists of places I’ve wanted to visit in Ireland for a few years. One of my majors I study while at Pitt is history with a European concentration. I've focused largely on Ireland, so this visit was incredibly interesting and relevant to my studies. The discussion in my classes involving the political prisoners in 1916 were some of the most memorable. The stories of the 1916 Rising and its aftermath are powerful. The jail's place in the present age has become so linked to the rebels who were executed in 1916 and I knew their stories would rise in the air. I was not expecting many of the feelings and sights within. I knew visiting the jail would affect me, but it's hard to describe how deeply sad and heavy the atmosphere is inside the jail. Hopefully my pictures and recollection can convey these feelings well enough.

I was lucky that one of the classes I was enrolled in for this semester is a politics class. In lieu of going to class one day, we were assigned to visit the jail (we didn't have to pay for tickets!), go on a tour, and write an essay about it. This felt like the best deal in the world, a chance to ditch the classroom for some hands on learning in a place that was number one on the "places I want to visit" list.

We started the tour walking briefly though part of the courtyard.

Our tour guide walked us out of the courtyard and into the jail's chapel. We sat down and listened to the first bit of history. The chapel has a special place in the history that's tied to the 1916 Easter Rising. Before his execution, Joseph Plunkett was allowed to marry his fiancée, Grace. No family or friends were around them to celebrate. They were accompanied solely by prison guards and a priest. Not long after the wedding, Joseph was executed. Grace never married again.

The altar in the chapel

After the chapel, the tour guide brought us through cramped halls with cells on one side. The walls featured peeling paint. It was cool and dark in many of these corridors.

A lock rests on the door of one of the cells.

Patrick Pearse wrote on the wall of this cell, "Beware of the risen people that have harried and held, ye that have bullied and bribed".

The tour guide continued taking us down various cells. Ones that held notable prisoners from the 1916 Rising were often marked with placards.

The sign above Countess Markievicz's cell.

Cells above our head

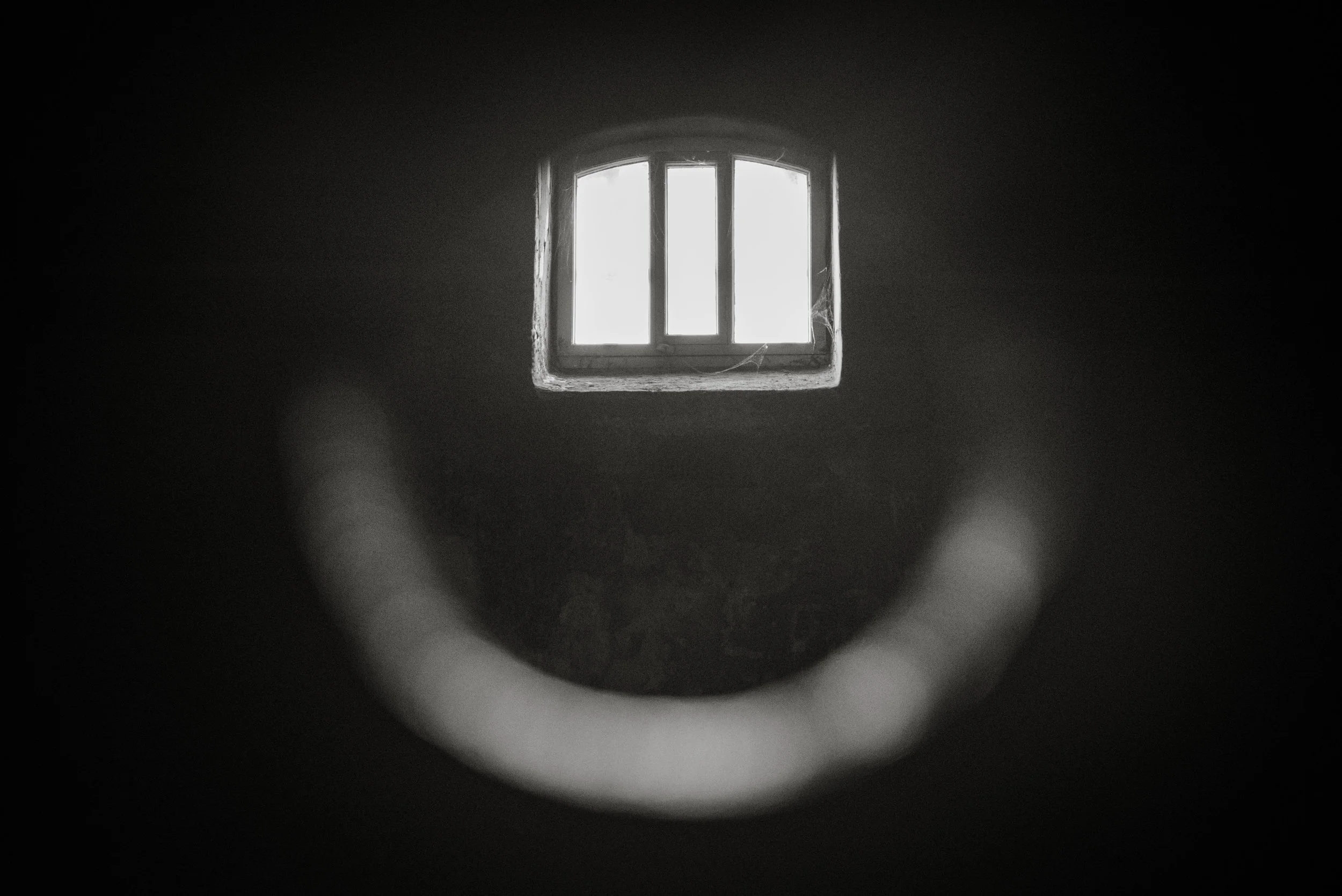

The cells had circular peepholes so guards could check in on prisoners.

We took a staircase down one level. They were uneven and worn.

At one point, the tour guide stopped us to explain a history beyond the Rising. This jail had been created over a hundred years before the Easter Rising (it opened in 1796) and also had a connection to the famine. Those found guilty of stealing food or begging on the streets could find themselves in a cramped jail cell or on a hall floor during this time period. The famine years saw an explosion in the prison population. The youngest prisoner held was a five year-old child during An Gorta Mor–The Great Hunger. Prisoners held during the famine were guaranteed at least one meal a day, which was more than many outside were guaranteed, but conditions were deplorable and disease was rampant.

You feel small and isolated walking through creaky floorboards and narrow passageways. I felt a heaviness lock around my heart and pull me down. It was not hard to feel history grab you by the ankles and drag you back to moments long since passed. You pass a cell with carvings outside it, initials, half-disappeared words and names from time. The doors are narrow passageways into the cells. You stoop and duck inside, the walls are suffocating. It felt like a thousand voices were calling out in the shadows.

I felt a myriad of emotions walking through the corridors, one by one. I felt as if I were trespassing, here for education, interest, study, holiday, but they were there for punishments, maybe just, many not. That young boy sent there during the famine was there for stealing food. And he, this little boy, hungry, distraught, possibly an orphan, would be placed among adults, men and women. Walking the corridors, this great injustice washed over me.

I felt these voices calling to me, begging for understanding, attention, comfort. How did it feel to be in a prison with only 100 cells at times when the jail saw 9,000? The filth. The discomfort. The crowding. You could lose yourself in a place so shut out from the outside world.

I could feel their stories clipping at our heels as we moved through. I felt like I understood blood sacrifices, how past deaths, how friends condemned to this life, could make me take up their cause. I knew I could leave at any moment, exit the tour and never come back. The men, women, and children who spent their time and sometimes end of their life could not so easily escape. And yet, even knowing I could leave at the end of the tour in an hour or right this minute, I still felt suffocated, isolated, a sense of fear.

Some cells held names of prisoners of note, many executed in 1916. Through a tiny hole you peak inside, and their world is at your feet. These men would have such a small space to breathe, think, sleep, stretch. You can feel their echoes in the air, like they never really left.

It was hard emotionally and spiritually inside the prison. The intention was to change the prison system, one prisoner to a cell (they failed at this at the beginning) and in their core philosophy believed in addition to solitude, that silence would be an important tenant of the prison. Their voices were a soft wave sometimes rolling against you and other times a thunderous call. They couldn’t be silent in death. The former prisoners' presence was everywhere.

Our tour guide, led us from the small hallways into the main room of the prison, the East Wing. Now, I have to preface that in the East Wing I saw something so strange that I'm still not sure I know what or who it was.

Our view stepping into the East Wing.

Those platforms would be used for guards.

The gaurds would have used this to quickly get to other levels if need be.

Joseph Plunkett's wife, Grace, was arrested during the Irish Civil War and painted this mural on her cell wall. You can see The Blessed Virgin Mary directly looking in through the peephole.

As we stood in the East Wing, the large curved room with a partial glass ceiling, we took pictures and wandered. In the doorway, where we would leave and where we had come in (pictured below), I saw a man in a suit swiftly moving past the frame of the door, beyond a window, and then he was gone. I looked around but no one else had seen him. I turned to Will, who also was taking the tour and in the politics course, speechless and unable to say what I thought I might have seen. It had to be a museum worker. As we exited the room, I looked down the corridor to where the figure had gone, but it was roped off with a “keep out” sign across it. How had he moved through that space so quickly and without pause? But the feeling pressing down, the history of suffering here, of last moments was real and true, so perhaps this could be too. Many days after the trip, I still question what I saw. I'm not a particular believer in the supernatural, and if it was a museum worker, they picked a strange area/bad time to walk by our tour.

Right beyond the spiral staircase is the entrance/exit.

After the East Wing, we were led down one more hallway and then out into the courtyard.

The high walls of the courtyard

It was a strange juxtaposition, these high, imposing walls that made you feel small with these bright flowers growing on them.

The tour guide moved our group into the execution courtyard, where those executed as a result of the 1916 Rising were taken. The courtyard was chosen as the execution location because it was the only area of the jail that prisoners could not see through windows, due to the high walls surrounding it.

The Irish Tricolor stands in the middle of the courtyard.

James Connolly was executed where the cross stands. He had been shot during the course of the Easter Rising in his leg and had developed gangrene. He was already dying from his wounds but the execution was ordered to go on. Because of his injuries, he was unable to stand so they tied him to a chair and shot him. When this story spread through Ireland, it infuriated the population. This turned the tide of public opinion to sympathy for the rebels and pushed them to martyrdom.

The spot where the other men were executed is marked by this cross.

A slight breeze picked up the flag as we stood in the courtyard.

We left the courtyard and ended the tour in front of the jail.

After the official tour, I headed up to the indoor museum which held more information on prisoners held and artifacts from those executed during the Rising.

Inside the museum at Kilmainham was one of the original Proclaimations.

I left the indoor museum and took two quick pictures.

As we exited Kilmainham Gaol, the feelings lingered but the oppressive bite of memories on the walls and in the air lessened. Still, my thoughts remained preoccupied with what I experienced simply walking through and what I thought I may have seen. It remains one of the most impactful and most memorable parts of my study abroad experience.